ON THE WEIGHT OF LIGHTNESS – SCULPTURE AS A FIELD OF PERCEPTION

Anthony Caro: Works from the Dieter Blume Collection | Christiane Löhr | Otto Boll: Works from the Artists' Studios

Through April 2025

The exhibition brings together three generations of sculptors who are advancing the dialogue between form, space, and perception in different ways – from Caro's pioneering steel constructions to Löhr's ethereal organic forms and Boll's almost immaterial sculptures.

Let the work speak for itself.

Antony Caro

Sculpture is an art of proximity – and at the same time, of distance. It appeals to us physically even before it reaches our minds. One cannot simply look at sculpture; one must walk around it, feel its weight, share its space. Only through the movement of the viewer does sculpture unfold as an event: in the tension between what the eye perceives and what the body senses.

This physical – spatial experience, central to modern sculpture, emerged from a radical break within early Modernism. When Pablo Picasso, together with Julio González, liberated sculpture from mass around 1930 – redefining it as a construction of line, surface, and space – they reoriented its essence from the corporeal to the spatial. This conceptual shift paved the way from David Smith to Anthony Caro, a lineage that continues to shape the field today.

As art theorist Ken Wilder has recently observed, true insight into sculpture does not arise from seeing alone, but from the moment when seeing becomes physical – as a “gain of blindness,” a knowing born of what eludes the gaze.[1] This interplay of distance and sensation, of optical and tactile experience, forms the conceptual ground upon which – in entirely different ways – the work of Anthony Caro, Christiane Löhr, and Otto Boll takes shape.

The works of these three artists move precisely along this threshold between the tangible and the visible, between materiality and immateriality, weight and suspension. And they share a subtle yet revolutionary act: the abandonment of the pedestal. By liberating sculpture from its traditional elevation, they dissolve the spatial and symbolic distance between the artwork and the viewer. The sculpture descends, becoming part of our shared space – occupying the same ground, the same air, the same physical presence. Thus, vision is transformed into a physical experience: the eye grows tactile, and space itself becomes resonant.

British sculptor Anthony Caro (1924–2013) was among the first to break down these boundaries consciously. His welded steel constructions rest directly on the ground – a radical rupture with centuries of sculptural convention. This shift redefines the relationship between viewer and work: the sculpture no longer stands before us, but with us.[2]

A former assistant to Henry Moore (1950–51) and deeply influenced by David Smith’s experimental approach, Caro marked a decisive turning point in the 1960s. He liberated sculpture not only from the figure but also from its architectural base. His works ceased to be compact bodies, becoming instead open structures of lines, plates, volumes, and voids. In doing so, Caro transformed sculpture from representation to constellation and from object to an event within space.

It is precisely in this openness that we experience what Wilder describes as “tactile seeing” – a way of seeing that seeks closeness rather than distance, incorporating the viewer’s body into the sculpture’s spatial field.[2] Caro trusts the eye but compels it to move, to perceive itself as corporeal: seeing becomes sensing; apperception becomes movement.

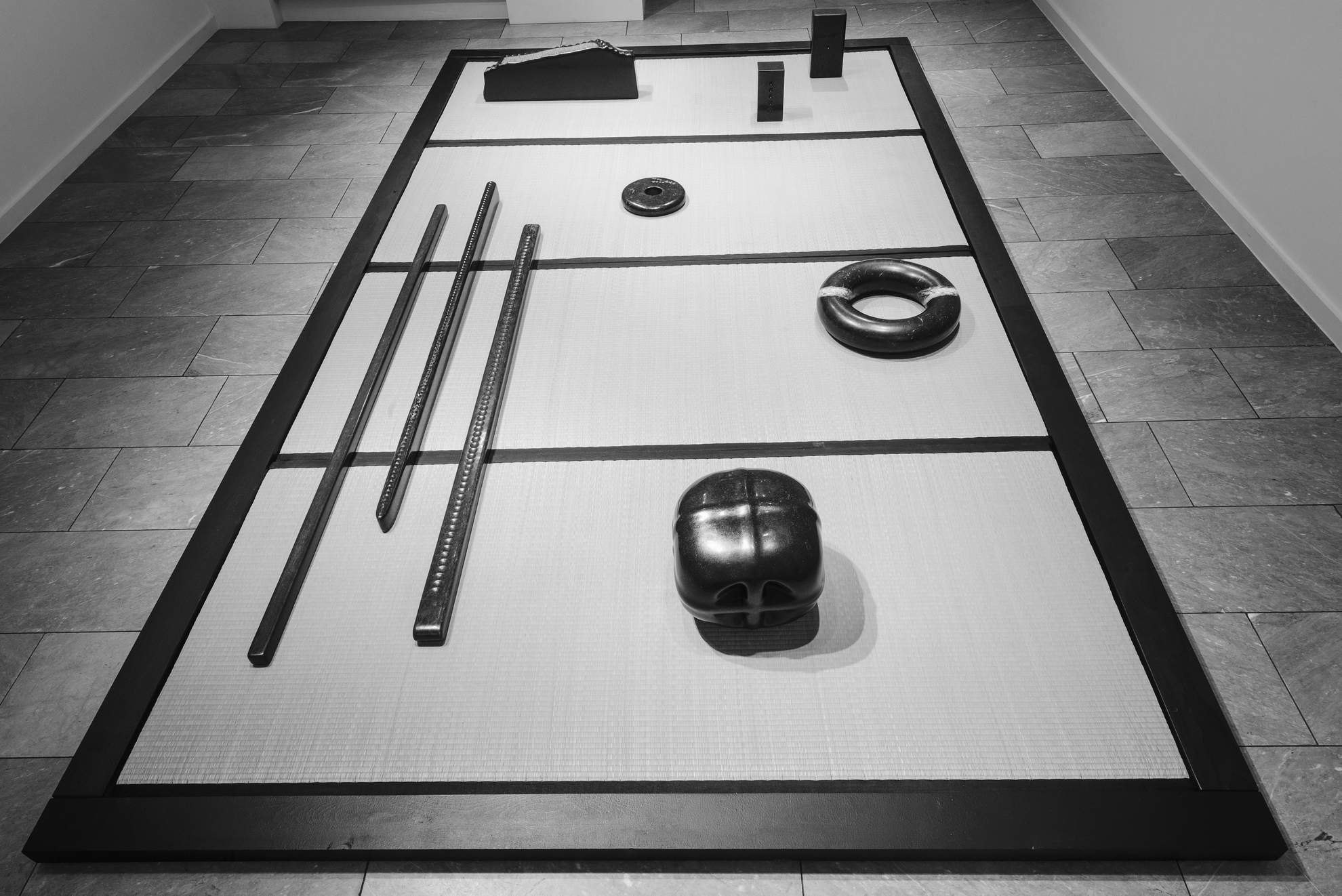

This dynamic is particularly evident in his so-called Table Pieces (from 1966 onward). These small-scale works, mostly made of welded steel, are not maquettes for larger sculptures but autonomous compositions. They actively incorporate the table on which they rest into their form – as a stage, boundary, and counterbalance – all at once. Their forms often extend beyond the tabletop`s edge, playing with gravity and balance, exploring the fragile boundary between standing and floating. Their smaller scale creates proximity and intimacy; the viewer is forced to lower their gaze, to approach, to follow. The table replaces the pedestal – not as a foundation, but as part of the sculpture`s conceptual space.[3]

Table Pieces on view in the exhibition come from the collection of art historian Dieter Blume (1952-2014) – editor of Anthony Caro`s comprehensive catalogue raisonné. Blume and Caro shared a long friendship and close intellectual exchange, reflected in Blume`s collection as well as in his academic work. This provenance gives the works a special art-historical significance – they are not only exemplary works from a pivotal period of Caro`s career but also embody a continuous dialogue between artistic practice and scholarly inquiry.

Caro conceived his works as visual compositions, as interplays of line, surface, and weight. Yet it is precisely in this visual rigor that a paradox lies: their impact cannot be grasped by vision alone. The body senses their forces, tension, their balance. This creates a form of tactile vision, a perception that occurs on the verge of touch. Caro`s work shows that even the gaze is a physical act – and that distance can be another form of closeness.

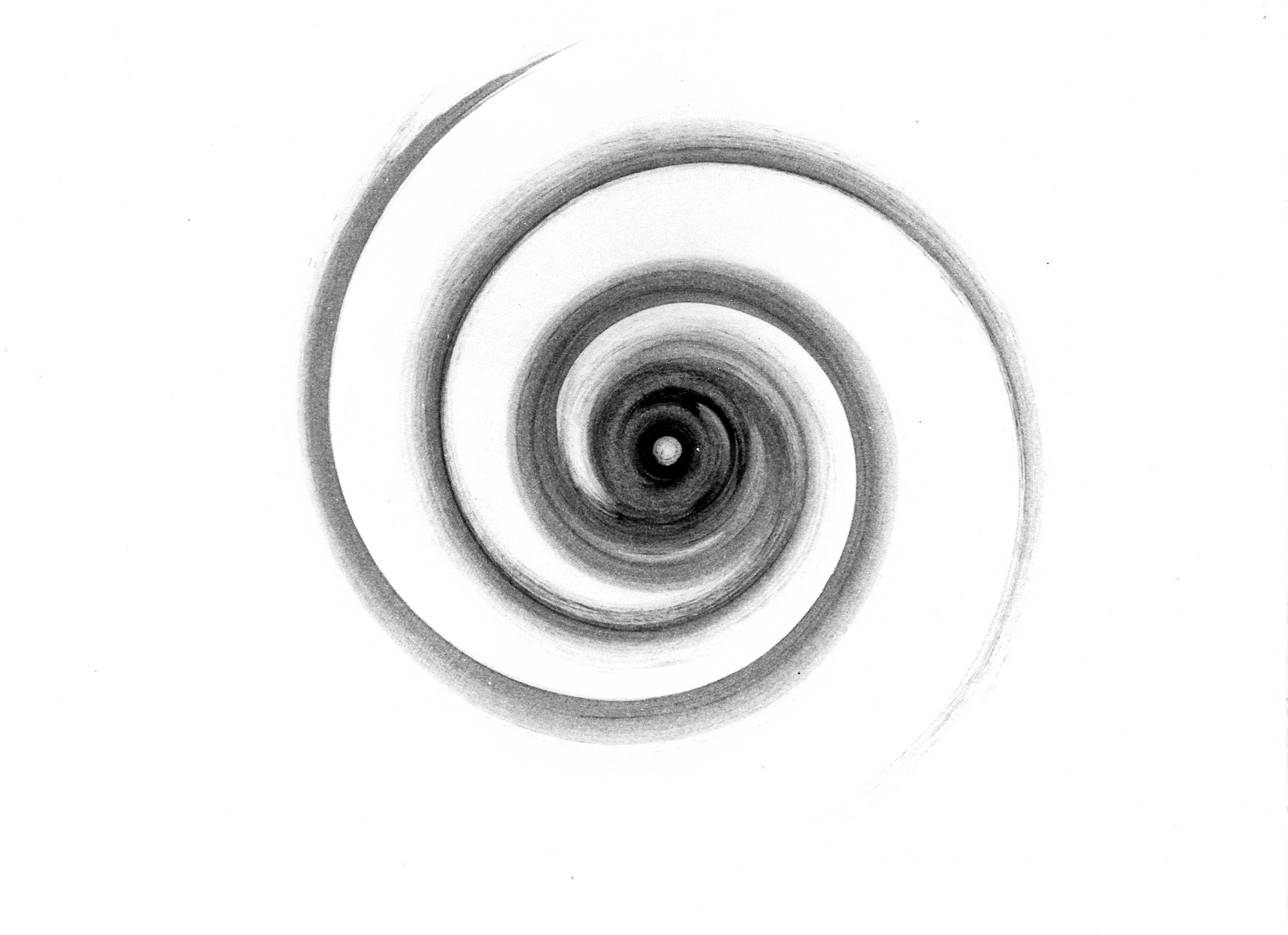

Christiane Löhr (1965), a sculptor and a master student of Jannis Kounellis in Düsseldorf, takes this relationship between body and space in a different, almost opposite direction. Her sculptures are composed of fragile, ephemeral materials such as seed heads, grasses, or horsehair. With architectural precision, she constructs delicate structures that hover between being grounded and floating in the air.[4]Löhr takes her material from nature and shapes it outside its original context into new, self-contained forms. Her works are not emulations but autonomous formal objects that arise from the organic logic of the material.[5]

Like Caro, Löhr also breaks with the traditional pedestal, but in a different, more subtle way. She uses wall- or floor-level presentation forms – small or large pedestals that gently support her sculptures without isolating them. Her objects grow into the space in which they stand or lie – they rest, balance, float. This creates a quiet, almost sacred relationship between the work and its surroundings: away from nature, from the physical to the metaphysical, and from the real place to the artistic setting.[6] They grow out of an inner center that unfolds outward in subtle movements—as in sacral architecture, where the idea itself materializes.[7] “I let myself be guided by the material and thus arrive at the form,” says Löhr. “It`s always about finding the form, and the process comes through the specific material. Essentially, there is a friction between the material and the work. ”[8]

This friction is palpable - not as a physical presence, but as a sensual one. Her works draw the eye, inviting it to see tentatively. Where Caro suspends the industrial, Löhr anchors the fragile. Her sculptures seem composed of air, movement, and memory.

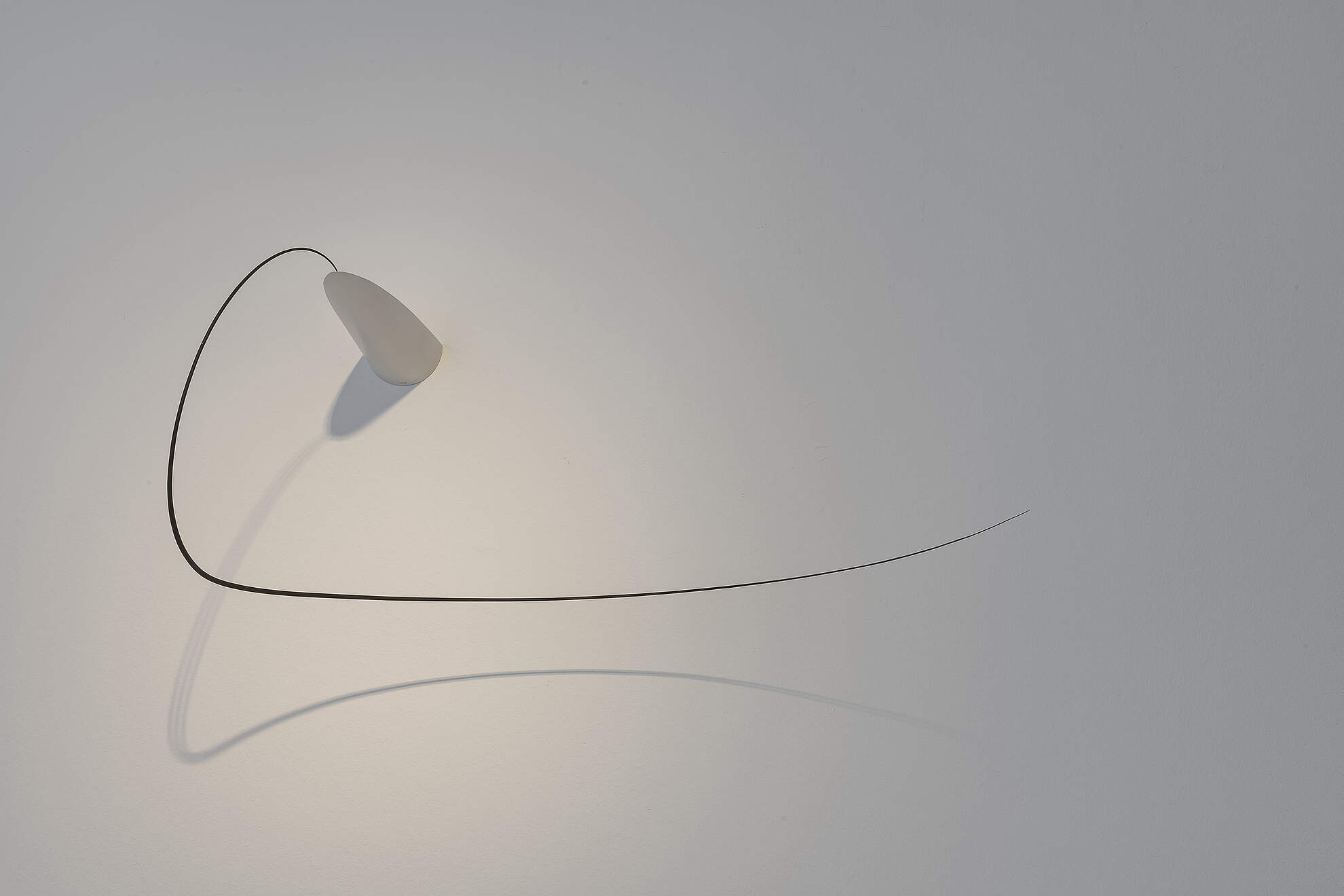

Finally, Otto Boll (1952) carries the dematerialization of sculpture into the realm of the nearly immaterial. His lines of steel, aluminium, or iron are so finely executed that they nearly vanish into space. Boll`s sculptures are not objects but events: they arise in the moment of observation, in the interplay of proximity and distance, light and shadow, appearance and disappearance.[9]

The viewer becomes an integral part of the work; it is through movement and changing viewpoint that form reveals itself. Perception becomes action; seeing becomes tactile. Boll himself describes this experience as “seeing with your fingertips,” as a physical awareness of space.[10] His sculptures demand an attitude of mindfulness, a visual tactility in which line and space define each other. In his work, steel – the epitome of industrial solidity – becomes weightless, dematerialized: a weight of lightness that only becomes apparent in the moment of experience.

Like Caro and Löhr, Boll also detaches the concept of sculpture from the idea of the pedestal. His works hang, float, and traverse the air. They are not monuments but movements of thought – “tools of seeing.”[11]Through this reduction, Boll achieves an intensity that recalls the classical while transcending it: a space of balance that is completed only through the viewer’s embodied perception.

Thus, for Caro, Löhr, and Boll alike, sculpture becomes both a school of seeing and a school of feeling. Their work embodies what Ken Wilder calls the “tactile turn” of modern art – a shift toward sensory experience as a form of knowledge. In this sense, their shared radicalism is not loud but quiet: it lies in translating the visible into a physical experience.[12]

At the same time, Caro, Boll, and Löhr span a panorama of sculptural thought across generations: from the radical revelation of sculpture in postwar Modernism, through the linear reduction of the late 1970s and 1980s, to a contemporary exploration of the balance between material and space. Their works – each in its own way – constitute an ongoing investigation of how form, weight, and lightness manifest themselves in space: a living tradition of seeing, feeling, and thinking.

Text: Noëmi Bechtiger

Bibliography

Bernardini, Anna (pub.): Christiane Löhr. Dividere il vuoto, exh. Cat. Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese, Cologne, 2010. | Caro, Anthony: Anthony Caro. Sculpture, London, 1975. | Celant, Germano: Christiane Löhr, Berlin, 2020. | Morschel, Jürgen: Entgrenzung des Kunstwerks als Gegenstand. Zu den Arbeiten von Otto Boll, das kunstwerk 4 (XXXVII), Aug. 1984. | Wedewer-Pampus, Susanne: Otto Boll: Found Objects / Display Tools, exhibition text, Dierking – Galerie am Paradeplatz, September 2020. | Wilder, Ken: „‘Touch-space’, ‘blindness gain’ and the ontology of sculpture“, in: Beyond the Visual: Multisensory Modes of Beholding Art, London 2025.

[1] cf. Wilder, 2025, p. 391ff. | [2] Caro, 1975, p. 14 f. | [3] Ibid.; cf. Wilder 2025, p. 391 f. | [4] Cf. Caro, 1977. | [5] Celant, 2020, p. 248-250. | [6] Ibid., p. 236-238. | [7] Ibid., p. 234. | [8] Bernardini, 2010, p. 39. | [9] Christiane Löhr in conversation with Noëmi Bechtiger, 26.11.2020 (unpublished). | [10] Cf. Morschel, 1984, p. 36, quoted from Otto Boll. Skulpturen / Sculptures, Cologne: Koenig Books 2019, pp. 30–36. | [11] Otto Boll in a letter to Jürgen Morschel, January 29, 2003, in: Otto Boll. Skulpturen / Sculptures, Köln, p.22. | [12] Wederwer-Pampus, 2020. | [13] Cf. Wilder 2025, p. 391 ff.

ON THE WEIGHT OF LIGHTNESS – SCULPTURE AS A FIELD OF PERCEPTION

Anthony Caro: Works from the Dieter Blume Collection | Christiane Löhr | Otto Boll: Works from the Artists' Studios

Through April 2025

Let the work speak for itself.

Antony Caro

The exhibition brings together three generations of sculptors who are advancing the dialogue between form, space, and perception in different ways – from Caro's pioneering steel constructions to Löhr's ethereal organic forms and Boll's almost immaterial sculptures.

Sculpture is an art of proximity – and at the same time, of distance. It appeals to us physically even before it reaches our minds. One cannot simply look at sculpture; one must walk around it, feel its weight, share its space. Only through the movement of the viewer does sculpture unfold as an event: in the tension between what the eye perceives and what the body senses.

This physical – spatial experience, central to modern sculpture, emerged from a radical break within early Modernism. When Pablo Picasso, together with Julio González, liberated sculpture from mass around 1930 – redefining it as a construction of line, surface, and space – they reoriented its essence from the corporeal to the spatial. This conceptual shift paved the way from David Smith to Anthony Caro, a lineage that continues to shape the field today.

As art theorist Ken Wilder has recently observed, true insight into sculpture does not arise from seeing alone, but from the moment when seeing becomes physical – as a “gain of blindness,” a knowing born of what eludes the gaze.[1] This interplay of distance and sensation, of optical and tactile experience, forms the conceptual ground upon which – in entirely different ways – the work of Anthony Caro, Christiane Löhr, and Otto Boll takes shape.

The works of these three artists move precisely along this threshold between the tangible and the visible, between materiality and immateriality, weight and suspension. And they share a subtle yet revolutionary act: the abandonment of the pedestal. By liberating sculpture from its traditional elevation, they dissolve the spatial and symbolic distance between the artwork and the viewer. The sculpture descends, becoming part of our shared space – occupying the same ground, the same air, the same physical presence. Thus, vision is transformed into a physical experience: the eye grows tactile, and space itself becomes resonant.

British sculptor Anthony Caro (1924–2013) was among the first to break down these boundaries consciously. His welded steel constructions rest directly on the ground – a radical rupture with centuries of sculptural convention. This shift redefines the relationship between viewer and work: the sculpture no longer stands before us, but with us.[2]

A former assistant to Henry Moore (1950–51) and deeply influenced by David Smith’s experimental approach, Caro marked a decisive turning point in the 1960s. He liberated sculpture not only from the figure but also from its architectural base. His works ceased to be compact bodies, becoming instead open structures of lines, plates, volumes, and voids. In doing so, Caro transformed sculpture from representation to constellation and from object to an event within space.

It is precisely in this openness that we experience what Wilder describes as “tactile seeing” – a way of seeing that seeks closeness rather than distance, incorporating the viewer’s body into the sculpture’s spatial field.[2] Caro trusts the eye but compels it to move, to perceive itself as corporeal: seeing becomes sensing; apperception becomes movement.

This dynamic is particularly evident in his so-called Table Pieces (from 1966 onward). These small-scale works, mostly made of welded steel, are not maquettes for larger sculptures but autonomous compositions. They actively incorporate the table on which they rest into their form – as a stage, boundary, and counterbalance – all at once. Their forms often extend beyond the tabletop`s edge, playing with gravity and balance, exploring the fragile boundary between standing and floating. Their smaller scale creates proximity and intimacy; the viewer is forced to lower their gaze, to approach, to follow. The table replaces the pedestal – not as a foundation, but as part of the sculpture`s conceptual space.[3]

Table Pieces on view in the exhibition come from the collection of art historian Dieter Blume (1952-2014) – editor of Anthony Caro`s comprehensive catalogue raisonné. Blume and Caro shared a long friendship and close intellectual exchange, reflected in Blume`s collection as well as in his academic work. This provenance gives the works a special art-historical significance – they are not only exemplary works from a pivotal period of Caro`s career but also embody a continuous dialogue between artistic practice and scholarly inquiry.

Caro conceived his works as visual compositions, as interplays of line, surface, and weight. Yet it is precisely in this visual rigor that a paradox lies: their impact cannot be grasped by vision alone. The body senses their forces, tension, their balance. This creates a form of tactile vision, a perception that occurs on the verge of touch. Caro`s work shows that even the gaze is a physical act – and that distance can be another form of closeness.

Christiane Löhr (1965), a sculptor and a master student of Jannis Kounellis in Düsseldorf, takes this relationship between body and space in a different, almost opposite direction. Her sculptures are composed of fragile, ephemeral materials such as seed heads, grasses, or horsehair. With architectural precision, she constructs delicate structures that hover between being grounded and floating in the air.[4]Löhr takes her material from nature and shapes it outside its original context into new, self-contained forms. Her works are not emulations but autonomous formal objects that arise from the organic logic of the material.[5]

Like Caro, Löhr also breaks with the traditional pedestal, but in a different, more subtle way. She uses wall- or floor-level presentation forms – small or large pedestals that gently support her sculptures without isolating them. Her objects grow into the space in which they stand or lie – they rest, balance, float. This creates a quiet, almost sacred relationship between the work and its surroundings: away from nature, from the physical to the metaphysical, and from the real place to the artistic setting.[6] They grow out of an inner center that unfolds outward in subtle movements—as in sacral architecture, where the idea itself materializes.[7] “I let myself be guided by the material and thus arrive at the form,” says Löhr. “It`s always about finding the form, and the process comes through the specific material. Essentially, there is a friction between the material and the work. ”[8]

This friction is palpable - not as a physical presence, but as a sensual one. Her works draw the eye, inviting it to see tentatively. Where Caro suspends the industrial, Löhr anchors the fragile. Her sculptures seem composed of air, movement, and memory.

Finally, Otto Boll (1952) carries the dematerialization of sculpture into the realm of the nearly immaterial. His lines of steel, aluminium, or iron are so finely executed that they nearly vanish into space. Boll`s sculptures are not objects but events: they arise in the moment of observation, in the interplay of proximity and distance, light and shadow, appearance and disappearance.[9]

The viewer becomes an integral part of the work; it is through movement and changing viewpoint that form reveals itself. Perception becomes action; seeing becomes tactile. Boll himself describes this experience as “seeing with your fingertips,” as a physical awareness of space.[10] His sculptures demand an attitude of mindfulness, a visual tactility in which line and space define each other. In his work, steel – the epitome of industrial solidity – becomes weightless, dematerialized: a weight of lightness that only becomes apparent in the moment of experience.

Like Caro and Löhr, Boll also detaches the concept of sculpture from the idea of the pedestal. His works hang, float, and traverse the air. They are not monuments but movements of thought – “tools of seeing.”[11]Through this reduction, Boll achieves an intensity that recalls the classical while transcending it: a space of balance that is completed only through the viewer’s embodied perception.

Thus, for Caro, Löhr, and Boll alike, sculpture becomes both a school of seeing and a school of feeling. Their work embodies what Ken Wilder calls the “tactile turn” of modern art – a shift toward sensory experience as a form of knowledge. In this sense, their shared radicalism is not loud but quiet: it lies in translating the visible into a physical experience.[12]

At the same time, Caro, Boll, and Löhr span a panorama of sculptural thought across generations: from the radical revelation of sculpture in postwar Modernism, through the linear reduction of the late 1970s and 1980s, to a contemporary exploration of the balance between material and space. Their works – each in its own way – constitute an ongoing investigation of how form, weight, and lightness manifest themselves in space: a living tradition of seeing, feeling, and thinking.

Text: Noëmi Bechtiger

Bibliography

Bernardini, Anna (pub.): Christiane Löhr. Dividere il vuoto, exh. Cat. Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese, Cologne, 2010. | Caro, Anthony: Anthony Caro. Sculpture, London, 1975. | Celant, Germano: Christiane Löhr, Berlin, 2020. | Morschel, Jürgen: Entgrenzung des Kunstwerks als Gegenstand. Zu den Arbeiten von Otto Boll, das kunstwerk 4 (XXXVII), Aug. 1984. | Wedewer-Pampus, Susanne: Otto Boll: Found Objects / Display Tools, exhibition text, Dierking – Galerie am Paradeplatz, September 2020. | Wilder, Ken: „‘Touch-space’, ‘blindness gain’ and the ontology of sculpture“, in: Beyond the Visual: Multisensory Modes of Beholding Art, London 2025.

[1] cf. Wilder, 2025, p. 391ff. | [2] Caro, 1975, p. 14 f. | [3] Ibid.; cf. Wilder 2025, p. 391 f. | [4] Cf. Caro, 1977. | [5] Celant, 2020, p. 248-250. | [6] Ibid., p. 236-238. | [7] Ibid., p. 234. | [8] Bernardini, 2010, p. 39. | [9] Christiane Löhr in conversation with Noëmi Bechtiger, 26.11.2020 (unpublished). | [10] Cf. Morschel, 1984, p. 36, quoted from Otto Boll. Skulpturen / Sculptures, Cologne: Koenig Books 2019, pp. 30–36. | [11] Otto Boll in a letter to Jürgen Morschel, January 29, 2003, in: Otto Boll. Skulpturen / Sculptures, Köln, p.22. | [12] Wederwer-Pampus, 2020. | [13] Cf. Wilder 2025, p. 391 ff.

ARCHIVE

21. Dec 2022 -

GANESHA & HIS HEAVENLY FRIENDS

13. Jun -

GE-MEN-GE-LA-GE | Africa, Bischoffshausen, Boll, Fontana, Goepfert, Girke, Kricke, Prantl, Rainer, South America, Verheyen

01. Feb -

West Africa | Rare, Unfamiliar, Masterful

GANESHA & HIS HEAVENLY FRIENDS

MASTERPIECES OF THE PICCUS COLLECTION, SAN FRANCISCO – BOLL | KESSELMAR | LÖHR - NEW WORKS

IMPRINT

© DIERKING 2025